Gaziantep & Edessa

Zeus and Europa Mosaic, Zeugma Mosaic Museum, Gaziantep

From Antakya (Antioch), I headed north and east, toward the foothills of the mountains from which flow the two great rivers of the Near East, the Tigris and Euphrates. I stopped in Gaziantep for lunch, as they say it has the best food in Turkey (and more sweetshops per person than anywhere else in the world). Pistachios were everywhere (they call it the Gaziantep nut in Turkey) I tried katmer for the first time, a dessert like baklava, but including clotted cream, with lots of bright green pistachios. This is the traditional breakfast after the wedding night, and I think they probably serve it in heaven.

Gaziantep also has a spectacular mosaics museum, part of a series of recent projects across the region associated with the GAP Project. The project created a massive series of dams on the Euphrates for electricity production and irrigation (more or less restoring those ancient canals that made the region fertile, but that were silted over the region became a Byzantine-Arab battleground 1400 years ago).

One consequence of the project was the creation of large lakes along the river, and in the process an amazing series of 2nd and 3rd century mosaics were discovered at Zeugma. They had been on the floors of villas for the elite in 253 AD when the Persians destroyed the city, and were largely untouched since then. The colors were vibrant and the forms quite sophisticated, and there are dozens of them. The museum is laid out on several levels, so many of them can be viewed from above as well as on elevated walkways.

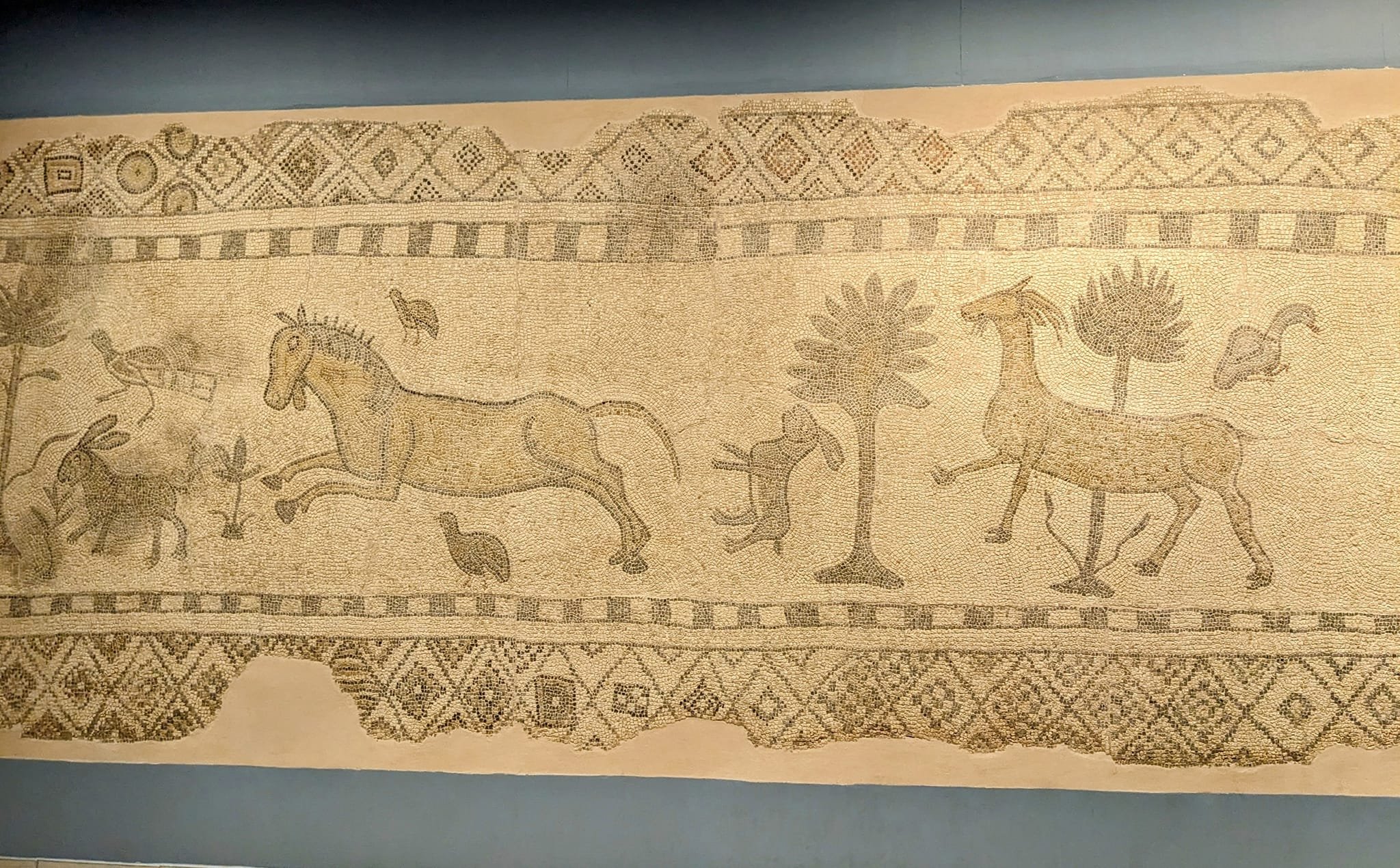

There’s also a great collection of Byzantine mosaics from the next few centuries. Many were of wild animals, apparently to represent the peaceable kingdom. It also was impossible to ignore that there’s nothing new about people wanting their names on things they donate at church. It was striking to me that many of these floors, which showed great craftsmanship, were decorations for village churches, in communities that were then and always have been tiny. The people wanted to give their best for God’s house.

I continued on to Sanliurfa, ancient Edessa, and stayed in a charming Ottoman house converted into a small hotel. Edessa has always been a very religious place—it was the intellectual center of Syriac Christianity in the ancient and medieval periods, and was famous for its extremist sects. It was more than half Christian on the eve of World War I. Now it’s entirely Muslim (my host in Antakya called it ‘the God city’), with very few unveiled women, and no wine on any menus. All the physical signs of its Christian past (and there must have been many) were erased decades ago.

The city, called Urfa in Syriac, is assumed by legend to be the Ur of the Book of Genesis, and thus the birthplace of Abraham. I visited the cave where he is believed to have been born (like the other sacred caves here, it also has a well), and couldn’t miss his fishponds.

They literally spring from another legend, which says that the evil Nimrod tried to kill Abraham by catapulting him from the two massive pillars that still stand on the ancient acropolis. The fish pools sprung up where he landed, and the enormous, well-fed carp that inhabit them are sacred by association. The fish pools are undoubtedly ancient, and may have originally been associated with a Syrian goddess whose temple was nearby. The survival of something as fragile as fish ponds for at 2500 years is surely remarkable in its own right. They are framed by several beautiful mosques and drew large evening crowds of families feeding them.

In the morning, I went to another site with Old Testament association, the Cave of Job, which is located inside a mosque complex on the outskirts of Sanliurfa. The local legend is that Job was an Edessan, a descendent of Jacob’s, and that he spent seven years in the cave tormented by his boils and impertinent friends, before God made a well to spring up, and when he drank of the water, he was healed. People still come to draw water from Job’s well in great numbers, and I pray it is a blessing to those who, like him, endure great suffering and temptation. I read Morning Prayer at the cave, and was struck by the aptness of the reading from Luke 4 on Jesus’ temptation.

Next, I visited Gobeklitepe, a Neolithic site excavated about 30 years ago on a hill outside of Sanliurfa. I’m generally not an enthusiast for prehistoric sites, but for its scale and great antiquity, this one was well worth the trip. The site is a series of circular temples, held up by massive monoliths (some as tall as 20 feet and weighing many tons). Many were carved with relief sculptures of animals and some had human features.

Constructed around 9500 BC, they are more than twice as old as the pyramids, and predate the development of pottery, agriculture, and the domestication of animals. The social organization and ingenuity needed to build such structures is hard to fathom. A film on the site pointed out that it had always been assumed before that agriculture produced civilization, and religion with it, but this suggests strongly that the process worked the other way around, as early crop cultivation may have come from the need to feed the large numbers of people who would gather to build and worship in such structures.

I continued on to Harran (Biblical Haran), where I visited the well of Jacob, where the patriarch saw and kissed his beloved Rachel. Like Urfa and Tarsus, Harran is an extraordinarily ancient city, and was once a grand place, thriving on the traffic of the Silk Road. A particularly despicable Roman emperor was murdered there, and the first mosque in Anatolia was built there, as well as the first Islamic university. The Byzantine walls largely survive, but it’s only a tiny village inside, with sheep and camels grazing among the stubs of pillars and blocks of ancient masonry.

There are huts with beehive roofs all over the village, a very ancient and weather-resistant form of house construction. I was led through a rather grand place built of about a dozen interconnected huts by a man of about my age who was born in them, when it was the home of his grandfather. He said that none are inhabited anymore, but some are still stables or storage sheds. Though picturesque, I guess they would be impossible to keep clean, and there’s quite a bit of new money about, with fields that had turned to desert being freshly irrigated all over the region around Harran.